Introduction

A

Prisons

Introduction

It has often been said that, apart from the military aspect

consisting in the war against the British, there was also

a civil war facet consisting in the conflict between Patriots

and Loyalists. For historians who wish to get an

understanding which goes beyond the enumeration of battles

and skirmishes the purely military features are not the most

interesting part because they mainly follow the rules of warfare

of that time: How many guns, cavalry and infantry on each side?

How to manage the procurement of powder, shells, carriages,

food, uniforms? How to recruit and pay the troops? How to reduce

desertions both in the militia and in the Continental Army.

All European countries in their endless wars were confronted

to these same challenges.

The last question is of course strongly connected with the

civil war aspects. Each side tried to recruit troops and

to identify the spies and recruiting officers sent by the other

side. We think that these aspects need to be studied

more fully and more systematically. This is particularly true

for the judiciary aspects, i.e. number of civilians

in custody, number of trials, number of banishments,

number of death sentences, number of pardons and executions.

It is the lack of global official judiciary data which

makes the task of historians exceedingly difficult.

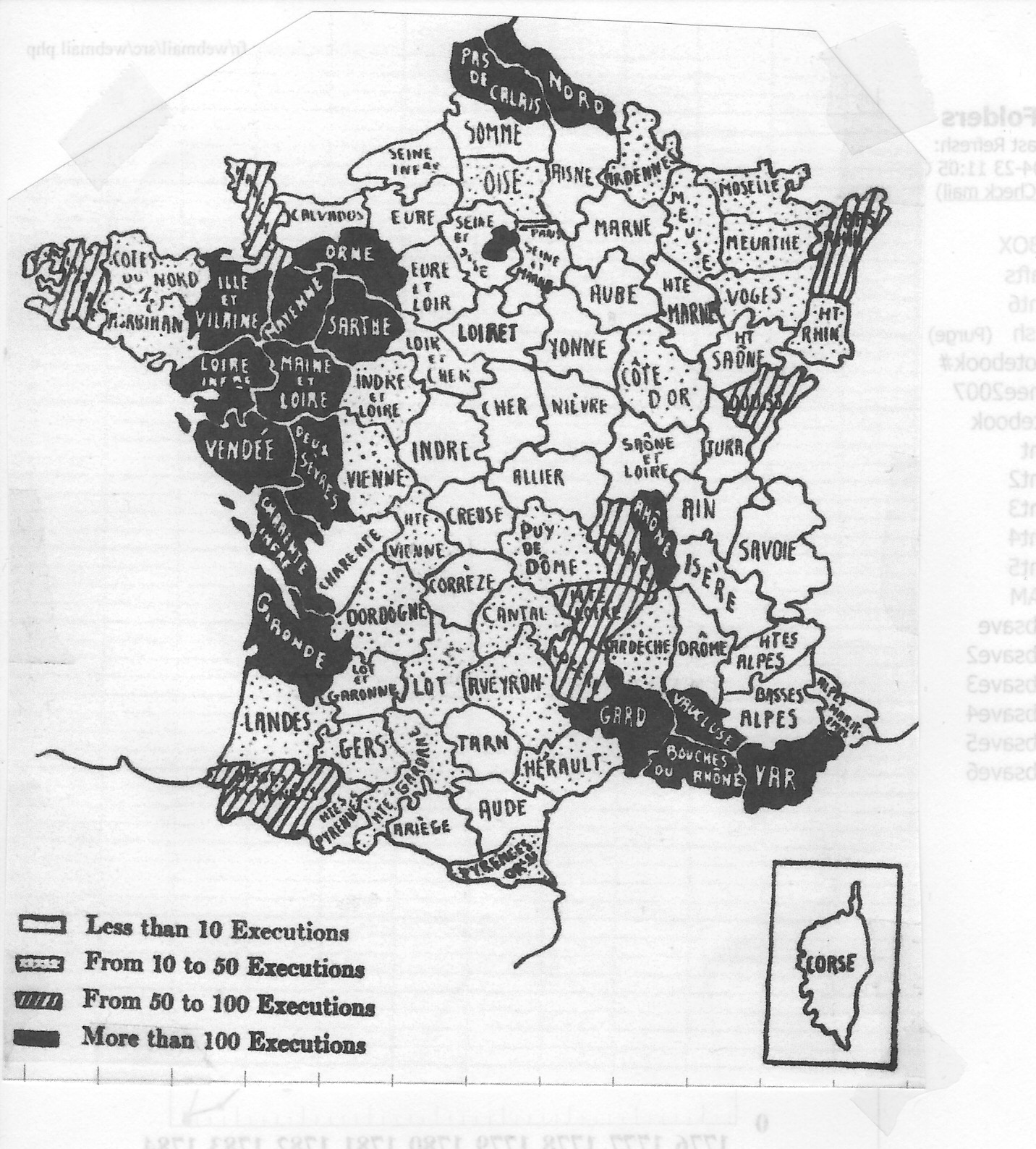

For the French Revolution there are official data of the number

of people arrested, tried, sentenced, executed. For instance,

in a book by Donald Greer there is a map of France with the

numbers of executions in each departement. It appears clearly

that these numbers are strongly correlated with the insurrections

of Royalists, the latter being

supported by France's neighbors and particularly

by England; see on the map the region around Toulon in the south

and the

region of the Vendee in the west and see also our

discussion below about the landing in Brittany.

In the Thirteen colonies there are no official statistics whatsoever.

Even for important data such as sentences of civil courts

or courts martial, no annual data were published.

In contrast the British have recorded data of the number

of prisoners of war in British custody

which allowed American historians to

estimate the number of fatalities on prison ships.

Prison ships have also existed on the Patriot side but for them

we do not have any data and therefore no death rates

can be estimated.

In several states suspected Loyalists were given the choice

between taking the oath of allegeance or staying in prison until

a possible trial several months later.

Only the

richest Loyalists could afford to pay 100 or 200 dollars

(or even more) for their security bond.

Naturally, nobody would expect the numbers of executions in America

to be in any way comparable to those of the year 1793 (called

Terror time) in France.

To begin with, there are two major differences.

These are certainly important factors but they are not

sufficient to explain the lack of data.

It seems that

in many cases the relevant data were lost. For instance,

we were told by archivists that in New York state

there are no remaining archives for the sessions of the

court of Oyer and Terminer (a court particularly

in charge of state trials). Often existing series stop in

1776: that is the case of the "American Archives" collected and

published by Peter Force. In Demond (1940,p.262) one reads:

"The state of North Carolina is almost destitute of source material

for the period of the Revolution" (except for what is found

in the Colonial and State Records which is limited).

So far we have under our eyes what can be called

a "patchwork" picture of the conflict between Patriots

and Loyalists. We use this word not only because

most of the studies are at state level but even at that

level one rarely finds data for key variables

(e.g. numbers of prisoners or trials) that are

global state level estimates.

Summary

Let us illustrate these three levels through a few examples.

With respect to mob violence.

(a) would consist in describing 3 or 4 events. (b) would

consist in recording ALL episodes of mob violence at least

in a limited area as documented in newspapers.

In (c) the events of mob violence would be recorded by police

or other state agencies (e.g. in present days, the FBI)

In his history of the Loyalists in South Carolina

Demond (1964) has a chapter entitled "Suffering of the Loyalists".

He uses the patchwork method described in (a).

He is well aware that this method is not satisfactory for

he tells his reader (p.119): "Throughout the latter part of the

war the district courts were most active in indicting the Tories

for treason and an indictment usually resulted in conviction."

An account based on all these trials would be close to the (b)

level. Certainly Demond would have tried this way if transcribed

records had been available. Later on in the book, Demond repeats the

same plea (p.152). "In 1782 when Faning [a loyalist leader]

saw his followers convicted of treason and hanged, in retaliation

he put to death his prisoners". However, this statement is not

supported by any evidence. How then does Demond know that?

Here our plan is to present those judicial data that we can

find and to attract attention on existing gaps.

Our study will be focused on few aspects but

whenever possible we try to propose

a fairly comprehensive and systematic view.

This is a plan which is neither easy nor comfortable.

It is not easy because usually the data that we need

are not available. It is not comfortable in the sense that we

will have to harvest our cases one by one with in addition the

unpleasant conviction

that many additional cases will not be caught in our net.

For instance it will take us much time and effort to

make a list of Loyalists who were executed whereas that information

should have been collected by the Ministry of Justice or,

in the case of court martials, by General Washington's headquarters.

To explain what we have in mind,

let us consider the question of the

mob violence against Loyalists or

officials of the British government.

It is known to have occurred repeatedly in northern colonies

and in fact it started well ahead of the American

Revolution.

Usually, historians limit themselves to the description

of a few cases.

Clearly, this cannot give a global view.

There is a world between

isolated attacks occurring say once a month and relentless

attacks several times a week. In the first case it may be just

an expression of popular discontent in the form of

practical jokes, whereas in the second it would create

an atmosphere of terror among the persons who are targeted.

An historical parallel would be the

attacks against opponents in fascist Italy.

In other words, depending on the frequency, the picture changes

completely.

The same observation holds also for many other

types of events. For instance, desertions do not attract much

attention unless they reach a degree which threatens the

very fighting capability of the army.

It is well known that there were collective trials

of Loyalists suspected of siding with the enemy. Courts of

Oyer and Terminer which had been commonly used in the British judicial

system for the trials of state prisoners had the same function

in the thirteen colonies and, after 1776, in the young republic.

There is so far no agreement among American historians

as to the frequency of such trials. Some hold that they

were rare, others describe a substantial

set of cases but add that anyway after being sentenced

all defendants were pardoned, especially when they had

been sentenced to death.

A third group of scholars wonders if the cases already known is not

just the tip of a large iceberg.

What makes such a study challenging is the

fact that so far judicial archives have been largely neglected by

historians, precisely perhaps because the question of dissent

was somewhat sidelined. If you search the index pages

of classical accounts of the Revolution you will not often

find the entry "Treason trials" or "Oyer and Terminate courts".

This

can be seen fairly clearly in the archives of Virginia.

Whereas in 1778-1779 one sees almost only issues

concerning military procurement,

in the early 1780s the part devoted to treason trials surged.

Probably there were also treason trials earlier but they

did not find their way into the records kept in county or

state archives.

In the following documents we try to shed some light on these

issues. The specific questions on which we will focus were

selected because we were able to find appropriate data.

In other words, our investigation was driven by data availability.

A

Prisons

The first document is a list of 50 prisons in use in the 13 colonies.

Why is such a list important?

Thus, if they were available, data giving the total population of

inmates would represent useful estimates of the strength

of the Loyalist population. Unfortunately, almost no

jail occupation data have been transcribed and published in

the vast movement that took place in the second half of the

19th century when the 13 states funded the printing and publication

of many historical documents. Prisoners of war have attracted much

attention but state prisoners did not. Naturally, it is

understandable that the very notion that there were state

prisoners, whose only crime was to be faithful to their

king, was perhaps not palatable for a nation

in which freedom is so highly praised.

B

Repression against Loyalists

In the same line of thought it is hardly surprising that

in American historiography

the repression against Loyalists is belittled or overlooked.

In this section we present two documents which

illustrate this bias. The first document is a 3-page article

(p.40-42) published in the "Canadian Loyalist Gazette".

Incidentally, it is worthwhile to notice that the illustrations

were chosen by the publisher of the Gazette, not by the authors.

The picture on the top of p.41 represents a person (meant to be a

Loyalist) hanging from a tree. At first sight this appears

to be in contradiction with the common view that mob violence

did not result in any death of Loyalists. Here, the fact that

the person is hanging from a tree obviously refers to mob violence

because in a lawful execution there would be a gallow.

However, this picture can be found on Internet and there

it has a caption

that says that it is not a person but an effigy. It was indeed

common to express hostility against someone by hanging his effigy.

Yet, that is not the end of the story because in Moore (1860,p359)

there is an episode in which a dissident minister is hanged by a

mob.

The account gives fairly detailed information.

The location is Charleston, the date is 1 December 1776, the name

is John Roberts. However the primary source remains unclear.

The following article is an extended version of the previous

paper.

C

Draft of "Forging consensus"

including a list of some 250 legal executions

The following document (220 p.)

It contains also an investigation of the fate of

Union citizens during the Civil War

who were in favor of a negotiated peace

with the Confederation. Like the Loyalists, these people

were considered as domestic enemies and often accused

of treason.

All these cases illustrate policies aimed at

forging consensus. Below we indicate a number of issues

considered in the manuscript. Once we have received some

feedback the manuscript will be completely rewritten.

Sorry for its present "untidy" shape.

What makes the American Revolution unique

List of executions (p.78) with indication of:

Name, Date of execution, State, Source.

Court martial sentences

Elusive consensus in the Civil War

Consensus forging in the First World War

References: archives, books, articles

The following file contains accounts of court-martials

in the Continental army. The source is a database and search

engine for letters exchanged by the Founders of the young

republic. It contains also "General orders" issued

at Washington's headquarters.

This database was set up by the National Archives

and the Library of Congress. The present compilation

is a very provisional version.

It can be noted that the army had also local headquarters

at state level or for theaters of war comprising several

states. Pardons (or reprievels)

could be issued by General Washington

but also by field Major Generals, particularly after 1778.

Death sentences issued by court-martials

E

Low key control of suspected Loyalists

How did Patriot investigations by various committees impact

the daily life of American citizens? Note that here we do not

restrict the question to avowed Loyalists for it will be seen

that even citizens who wanted to stay "neutral" were ordered

to appear before the committees for questioning.

For historians the challenge is to find a source describing

the daily interaction between the population and the

investigations conducted by the Patriots. Here the important

word is "daily". The records of the various committees give

some information about their work but most often what is

reported is a selection of the activity of the committee.

Incidentally the term "minutes" that appears in the titles

of such archives is a misnomer for they are rather

summaries.

However what we are looking for seems to

exist in the archives of Albany county. Victor Hugo

Palsits, the scholar who edited these archives, tells us

in his introduction that in all other counties of

New York State such archives may have existed but were

lost or destroyed. His own words are as follows.

For Albany county there are 4 volumes totaling 1,071 pages.

The first two cover the period: 17 Oct 1776 - 12 Oct 1777

whereas the last two cover: 15 Apr 1778 - 13 Aug 1781.

The information provided by these volumes was compiled and

arranged into a standardized form comprising the following

columns:

This standardization will enable us to count the

interactions between the Committee and the citizens

and to see its evolution in the course of time. It will

be seen that altogether in Albany County almost 50% of

adult males came in contact with the Committee for

one reason or another.

As more and more Loyalists were imprisoned,

moved to New York or went abroad

one would of course expect the "density" of Loyalists

in the free population to decline and this is indeed

what is observed.

The number of monthly "collisions" decreases from 170

in 1776 to about 50 in 1780. Note however that there is a bias

in the sense that in the course of the war the conflict

moved from the northern states to the south. If a similar

study could be done in the south it might reveal an

increase rather than a decrease.

Naturally, it is not surprising that the events occuring

in Albany County also reflect the major events of the conflict.

A clear illustration is the fact that in Oct 1776

some 120 prisoners were sent from New York State to the

town Exeter in the state of New Hampshire. This suggests

that Exeter had a prisoner camp with a high capacity.

F

Number of imprisoned Loyalists

Estimate of the number of imprisoned individuals derived

from Loyalist compensation claims

As already observed despite the fact that there were

over 50 prisons in the northern states (see above)

almost no prisoner list records are available. As there were

town jails, county gaols and provincial prisons such archives

should be available at various levels. It is possible that

lists of prisoners are still hidden in the archives just waiting

for historians to get interested in them. An alternative

explanation would be that, for some reason, they were

destroyed. Actually, the two explanations do not

exclude each other. Lists of prisoners (or merely counts) would

constitute direct evidence. Lacking that one needs to resort

to indirect evidence. Such an attempt was conducted in the

following paper by one of the few American historians who took

interest in this issue:

O'Keefe (K.J.) 2021: Mass incarceration as Revolutionary

policy: the imprisonment of Hudson Valley Loyalists.

Early American Studies pp.495-527.

Here we try another method in order to see if it

leads us to an estimate that is consistent with

the result obtained by Prof. O'Keefe.

During and after the war, many individuals who had been

denounced as "having assisted the enemies" became

refugees who settled abroad. Starting in May 1778,

long lists of suspected

Loyalists had been published. In Pennsylvania, for instance,

they comprised nearly 500 names. More details can be found in

the "Forging consensus" manuscript mentioned above.

Among these refugees those who felt that they they had really been

faithful Loyalists (and could prove it) presented demands to the

British Claim Commission. A compilation of many (but not all) of these

claims was published in 1980 in the following book:

G

South Carolina Loyalists

Needless to say, even before independence,

the Loyalists in northern states were submitted to considerable

pressure. Many cases are reported of Loyalists being pushed

to departure by mob violence.

Then, in the face of a threatening British invasion

but before the city was duly occupied,

it made sense to remove from New York

all those suspected of being "disaffected".

In the following months

all farmers whose property was considered too easily accessible by sea

were relocated farther away from the seaside.

The same scenario was repeated when British forces threatened

and eventually invaded Philadelphia, then the largest American

city.

What then made the invasion of South Carolina so different?

Many answers could be proposed but one obvious difference is

that in the north the British troops remained confined in

the cities and did not try to support the Loyalists in the few counties

surrounding New York (or Philadelphia) where they were a majority.

In SC, on the contrary, the British and Loyalist troops tried to

hold the whole state. In order to ensure local visibility they

needed to create militia companies formed of Loyalists.

Thanks to the presence of their troops not far away the British

could enlist even reluctant Loyalists. In the north,

recruiters were also sent from New York to neighboring counties,

but in SC this was done on a much larger scale and that is how

the confrontation really became a civil war.

For instance, we

are told that at the battle of Kings Mountain

(7 Oct 1780) there were only few British troops, most of the fighting

force consisted in Loyalists. The same observation holds for the

battle of Kettle Creek (14 Feb 1779).

Nothing similar can be seen in the north for the obvious

reason that it took time to organize, arm and train companies

of Loyalists.

In short, from a military perspective, in northern states

the Loyalists were never a real threat.

Between 1775 and 1779 there were already SC Loyalists but they were

weak and exposed to Patriot repression. With the perspective of

the arrival of British forces (including Loyalist regiments)

by sea as well as by land, the perspective changed completely.

A parallel with the French Revolution may be useful.

In 1792 the first violent protests in the region of Vendee

were triggered by the introduction of

conscription which itself was in

response to Prussian and Austrian armies threatening the

north east of France.

At that point the situation

was still manageable. Protests against conscription are

not something unusual. After all, the protesters had no cannons

and probably only few (fairly outdated) guns.

The situation changed

completely when, thanks to English support, the protesters

got weapons and were able to form military units led by experienced

officers from the nobility.

In addition, the British fleet was never far away allowing

English occupation of a number of offshore places (e.g. Noirmoutier,

Belle Ile) and threatening to land

an expeditionary force of rebels, which indeed happened in June 1795.

(see below).

H

Hunting down Loyalists

Hunting down Loyalists in South Carolina:

the logic which led to the treason trials

According to present knowledge, there have been only relatively

few treason trials in the northern states. A number of them

were listed and described earlier. We made a distinction between

civilian courts and court martials. Following British rules,

treason trials were tried at courts of Oyer and Terminer (O&T).

There were courts of O&T in Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey, New York,

and Pennsylvania. In the other states there were similar courts,

e.g. Supreme Courts of Judicature or Courts of General Session.

It seems that almost all the archives of the courts of O&T have

disappeared. An archivist of the New York state archives told us:

"The only documents produced by Courts of O&T were minute books and

none survived for the period of the Revolution (1775-1782)".

We got similar answers in several other states.

I

Parallel between SC and the Vendee

Drawing a parallel between the war in the Vendee (1792-1793 and 1795)

and the war of independence in South Carolina is not absurd for

the following reasons.

(1) Militarily, the big event was the landing of June

1795 in Quiberon

which involved some 26,000 troops on each side; this was a

close parallel of the invasion of Charleston

Moreover, this

action was preceded by the Vendee

guerrilla warfare which was similar, albeit less

violent, to the repression against the SC Loyalists in the years

1775-1779.

(2) In SC the landmark event was the siege and taking of Charleston

by the British

in May 1780. It involved some 6,000 troops on each side.

The British invasion of Quiberon in Brittany consisted in two

successive landings separated by an interval of one week.

A description of the landing force gives an idea of its strength.

Consisting in 60 transport ships protected by 9 warships, it

brought military equipment for about twice as many soldiers than those

on board. The intent was to deliver this equipment to

the insurgents who would join the rebellion after its first victories.

(3) In SC to change allegiance was not uncommon, both among the

population and among the troops. This raised the question

of whether someone should be seen as a Patriot, a Loyalist,

a traitor or a POW.

It is known that hundreds of defeated troops were tried by

makeshift Patriot courts and that a number of them were

sentenced and hanged.

The defeat of the expeditionary force in Quiberon raised the

same question.

Apart from the Royalist emigres, French soldiers held as prisoners

of war in England had been incorporated into the invading force.

After its defeat they could have been treated as traitors

but in fact most were pardoned.

Many of the Royalist emigres were taken back to

England by the fleet but for those who became prisoners, it was

another matter.

Some 300 of them were tried as traitors, sentenced and executed

by firing squads. At that time such a move was

not unusual as attested by the similarly bloody

repressions which followed the Monmouth rebellion in 1685

(after the defeat at Sedgemoor)

or the Jacobite rebellion in 1746 (after the defeat at Culloden).

J

British goal in the Brittany landing

Contrary to superficial accounts, the primary purpose of the

landing of a British expedionary force in the south of Brittany

was not just to help the Royalists and Chouans

(i.e. disaffected).

The real goal was to trigger a mass

insurrection which would take the city of Rennes

and occupy the north-western part of France. That, it was hoped,

would bring down the Republican government and permit the return

to power of Louis XVIII. This thesis is confirmed by the fact

that the 60 transport ships brought equipment for many more

soldiers than those taking part in the landing, for instance 60,000

shoes, 35,000 muskets, 17,000 infantry uniforms and

5000 cavalry uniforms (Champagnac 1989)

Another indication in the same direction is the participation of

British troops. Three infantry regiments (90th, 19th, 27th)

representing some 4,000 troops were on board with the first wave,

although it does not seem that they took part in the action.

Had the action in south Brittany been successful, the plan was

to make a second landing with 10,000 British troops

in north Brittany in the intention

of taking the port of Saint Malo.

K

Civil war features of the Revolution in South

Carolina

It is often said that in South Carolina the conflict between

Patriots and Loyalists took the form of a civil war.

However in historical accounts one finds only few facts which support

this assertion. One key feature of SC was the the existence of

a fairly strong minority of Loyalists which, quite naturally,

was amplified by the British occupation of Charleston.

A comparison with Massachusetts may be useful because

in contrast this state had one of the weakest Loyalist population.

It is said (see Maas 1989) that only 2% of the adult population

refused to sign the Association Act of 1776. Nevertheless in the

same book by David Maas there is a chapter entitled: "Legislative

efforts to purge the Tories in Boston". This was of course the

objective pursued by the Patriots in all states, but a policy

which may work against a tiny opposition may not be suitable

in states where the Loyalists formed a substantial opposition.

In Massachusetts, one half of the Loyalists departed when the

British forces evacuated Boston on 17 March 1776.

Yet, as soon as 26 March a list of 85

so-called "inimical" persons was set up and sent to the General

Court where 7 justices of the peace would be in charge of

interrogating the suspected Loyalists. Their decision would

imply release, confined on bond or held in jail until a possible

trial that might take place several months later. The threat of

being held in prison was real as shown by the fact that of

16 persons brought to trial by the militia

in April 1776, 5 (Charles and Miles Whitworth,

William Perry, Benjamin Davis, Thomas Edward) were placed in

close confinement in Boston jail (Maas p.181). As an example of

the verdicts deivered at the trials one can mention the case

of William Gardiner who was sentenced to banishment (Maas p.256),

a sentence that the legislature changed into one year in jail.

In SC between 1775 and 1778 the Loyalists had suffered under

Patriot repression but as soon as British forces

(which included regiments of Loyalists) drifted toward

the Carolinas the Loyalists started to form local militias.

This had two consequences.

(i) It was no longer possible

to bring suspected Loyalists to prison or to trial.

(ii) Once armed, Loyalists could oppose force to force..

From a mere police operation, the conflict became a real civil war

with the result that the Patriots themselves felt threatened.

Fear generated harsher actions.

When taken prisoner armed Loyalists were often summarily executed or

tried by "special" courts often composed of officers (as

in the trials following the battle of Kings Mountain) but which

were not regular court martials.

This trasformation raised also a major difficulty for historians

that we explain in the following section.

How to narrate civil wars?

The narration of civil wars raises the same difficulty as already

mentioned for mob violence. In a large country like the United

States there are at any time incidents in which police

officers or federal agents are killed. However, nobody would

call that a civil war situation. On the other hand the American

Civil War did not immediately start with large battles; at

first there were skirmishes. In North and South Carolina

the War of Independence consisted in fairly small battles.

The fall of Charleston which was certainly the largest involved only

some 3,000 Patriots; in addition the attackers were British troops

rather than Loyalists. The largest involment of Loyalists was

probably at the battle of

Kings Mountain. Although it was assuredly an important battle,

there were only a few hundred soldiers on each side.

Is that enough for calling it a civil war?

Below we examine how well known historians have narrated

the civil war aspects of the war in the Southern states.

L

Epuration of the Loyalists

This process of radicalisation was marked by the steps described

below

Special court created to try Loyalists

On 20 Feb 1779,

reacting to the threatening British

invasion, the SC General Assembly passed an Act which gave 40 days

to the citizens who had joined the enemy for surrendering unless

being liable to the death penalty. Manned by

Thomas Heyward and John Mathews, a special court was set up to

try all persons charged with sedition. (Lambert p.81)

Execution of spies in Charleston

It seems that the first application of the new law was made

during the siege of

Charleston. Thanks to the fact that Thomas Heyward was one of the

signers of the Declaration of Independence its biography can be

found on Internet and there we read that he presided at the trial

and condemnation of some Loyalists charged with treasonable

correspondance with the enemy. They were executed in sight of the

enemy lines. The biographty does not tell us how many were

hanged nor does it give the date(s) of the hangings.

Somewhat independently one learns that

on 17 March 1779 also in Charlestown William Tweed

and Andrew Groundwater were hanged. Was their trial

part of those presided by judge Heyward?

Trial and executions at Ninety Six

Robert Lambert (p.83) tells us that in March 1780

no less than 150 prisoners were waiting for their trial

by the newly created special court.

A number of them were Loyalists taken prisoners at the battle

of Kettle Creek in Georgia and who had been marched in chains to Augusta,

a distance of about 200km. The information available about the

trial is quite sketchy. There was a clerk (we even know his name)

but the records did not survive.

The trial lasted

21 days from 22 March 1779 to 12 April which means that on average

20 persons were tried daily (including on Sundays). Eventually,

all except 5 were released or reprieved in the sense that if caught

a second time on the British side they would be executed

immediately.

It turns out that holding trials at Ninety Six was not uncommon.

It was a village of only few houses but which had a jail ans a

courthouse. According to Robert Davis (p.175), in 1778 there

had been trials

of Loyalists and "at least one execution, that of a man named

Allen". One suspects that such a cryptic sentence does not

rely on an appropriate primary source for otherwise

more information would be available (date, complete name of the;

person named Allen.

Other trials of Loyalists were held in Salisbury, North Carolina

on 15 Sept 1779 (Davis p.180). We are told that several [how many?]

Loyalists were sentenced to death and that all were granted reprieve

except two, namely Captain Samuel Richardson and Lieutenant William

Armstrong who were hanged on (or around) 5 November 1779.

Summary trial and executions after the Patriot victory at Kings

Mountain

Following the American victory at Kings Mountain against a militia

of Loyalists, there was a summary trial in which 30 were sentenced

to be hanged but only 9 were actually executed.

Death march after the Patriot victory at Kings

Mountain

Excerpt of the Royal Gazette of 24 February 1781

The executions are reported

in all accounts. In contrast the march which followed did not

attract the attention of historians to the same degree.

As a matter of comparison one can consider the "Bataan Death March"

in April 1942 for this is a case for which there are some data.

Some 60,000 Filipino and 15,000 American prisoners of war

had to march from Bataan to their prisoner camp some 100km

away. The number of American deaths is fairly well known and is

around 500 which represents a rate of 3.3%.

The Filipino deaths are more uncertain (between 5,000 and 18,000);

if we take 10,000 as a rough estimate, the death rate is 17%.

It should be added that the march took place after a siege of

3 months. For the 700 POWs of Kings Mountain a death rate

of 3% would have led to 20 deaths. Naturally the conditions

differed greatly but at least this number gives an order

of magnitude in the sense that one can be sure that the

real number is not 10 times smaller or 10 times larger.

According to Allaire, the rebel officers would often came among

the prisoners, draw their swords and wound "those whom their

wicked mind prompted".

Lt Allaire reports that on 17 oct 1780 three prisoners attempted

to make their escape. Two succeeded but the third "was shot through

the body".

In a general way suspected Loyalists were often led on long

marches. For instance in November-December 1776 some 230 Loyalists

of New York state had to march 300km to Exeter in New Hampshire.

Other NY Loyalists were sent to Massachusetts, Connecticut and

Pennsylvania. As 35km/day can be considered as

a reasonable assumption of average velocity a march of 300 km

would last some 9 days. In the mid of winter, probably with

little food and rudimentary shelters during the night,

one would like to know the death rate for weak and

elderly persons.

In all American

accounts of the long marches faced by British prisoners

of war

there is a marked tendency to attribute melting numbers to escapes

rather than to deaths. The fate of the Convention army

(consisting in prisonrers made at Saratoga) is another

illustration.

The so-called "Trials of Tears" of native American Indians

come to mind. In the 1830s they were led from various locations

to the state of Oklahoma, i.e. west of the Mississippi. Often

such marches took also place in winter time. One reads

that this was the request of the Indians themselves,

supposedly in order to avoid the risk of diseases. Whether it

was a wise decision is to be seen.

Later on, in the 1880s and 1890,

the western Indians were marched to their reservations often

after being kept for several months in stockade camps in bleak

conditions. It was not uncommon that they were transferred

from one temporary reservation to another before being eventually

settled in a more permanent place.

M

The spiral of retaliations

In December 1780 General Cornwallis declared: "Rebel parties

have so terrified my people that I can get nobody to venture

far enough out to ascertain anything".

The reason given by Robert Lambert (p.200) is so uncertain that it makes

the reader uneasy. He says: After Cornwallis left South Carolina

many of the British posts in which Loyalists served were taken

by the Patriots. After the Loyalists were confined,

it happened that some of them were set aside and hanged

or shot individually or in small groups. This is of course a very

serious assertion. If Lambert had some supporting evidence he

should give it to his readers. If he had none it would be better

to omit such a statement.

It is true that in the subsequent pages he cites some

cases, but in small number. Here are two illustrations.

When Fort Motte surrendered Tory Lieutenant George Fulker and

John Jackson were hanged.

After Patriot General Thomas Sumter captured Orangeburg 14 prisoners

who were being escorted to the camp of General Greene were

executed. The shooting became known because one of the victims,

militiaman Joseph Cooper, who was presumed dead in fact had survived

(Lambert p.201)

Contrary to the previous one which concerned only individuals,

this episode is a mass shooting of the kind described above.

However the event is described in two lines only and

without indication of date. It is reported that the shooting

occurred in the

Fisher regiment but this was not of great interest because

Lt-Col John Fisher was in charge of all the troops in Orangeburg.

N

List of names of 300 Loyalist victims in SC

A petition dated 19 April 1782 was sent by American Loyalists

to Lord Germain who was the minister of George III in charge

of the American war. The petition was signed by 11 officers from

the Ninety Six and Camden districts.

In an appendix the petition contained 300 names of Loyalists

said to have been "massacred" or "murdered" (depending on the version)

in the district of Ninety Six.

The terms "massacred" or "murdered" mean that they were not

killed in regular battles. The list is available on Internet

but one should pay attention to the fact that there are several

versions. Although the names are the same, the comments which

introduce and follow the list may be somewhat different.

O

Names of Loyalists in the NY state counties of

Albany and Queens

P

Evolution of desertion

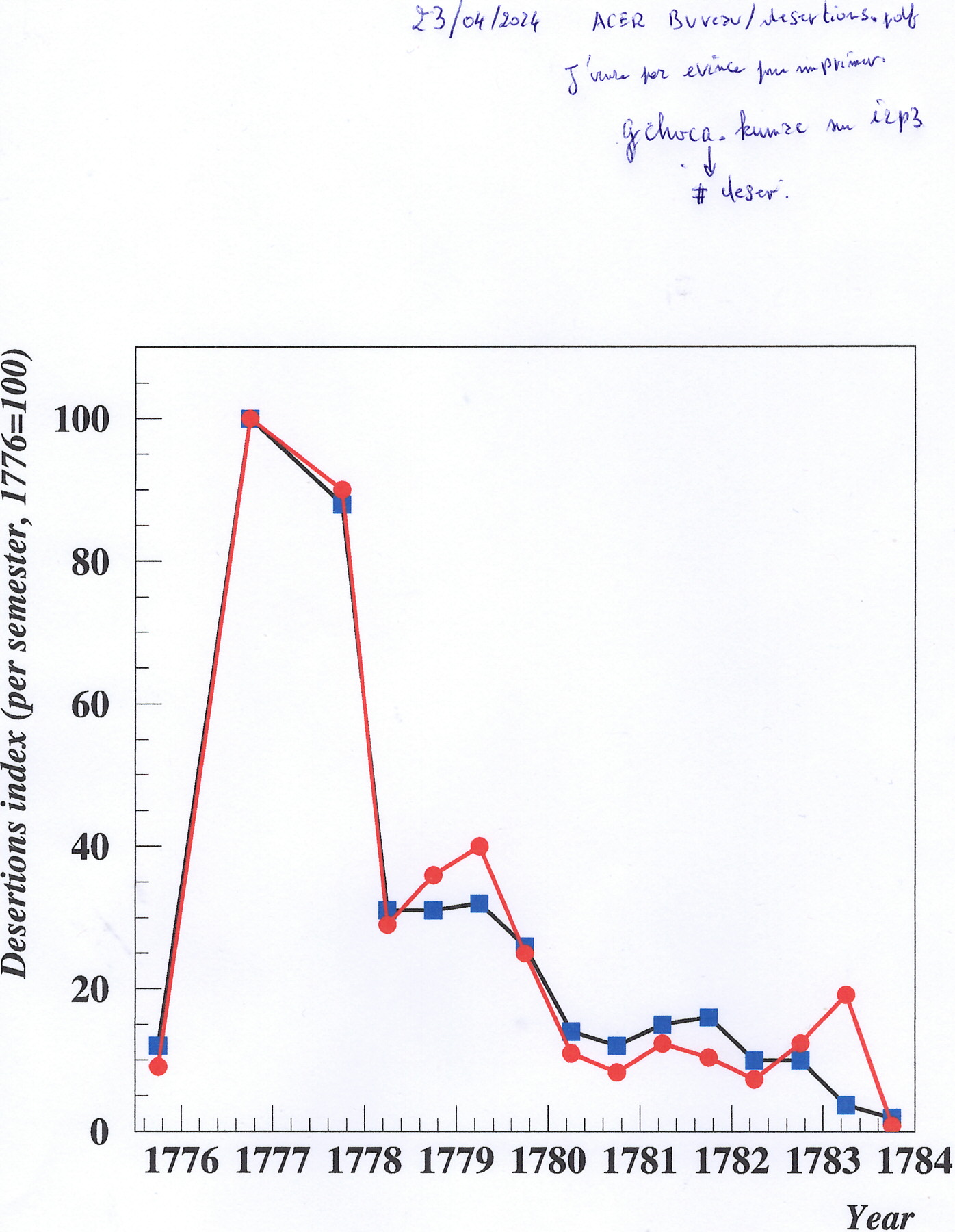

The fall in the number of desertions is impressive but before we

try to find how it should be interpreted we must answer the two

following questions:

(i) Do our data concern the militia or the Continental Army?

(ii) How were these estimates obtained?

Answering the first question is not easy because the

articles mentioning the desertions indicate only rarely

the origin of the deserter. The desertion estimates

were obtained thanks to the fact that

when a private deserted, one of his officers would ask a newspaper

to publish a search notice offering a reward to any person

giving information that may facilitate his arrest.

In Boyle (2009) the author has collected all such notices. Together

with their date of publication these articles

give a chronological list of the desertions. This list can then be

explored in two ways (i) By counting the number of pages

for a given time interval. This leads to the curve in blue.

The first point corresponds to a moment when the Patriot army

was only coming into existence. After this initial point the desertions

jumped to a high level after which they declined steadily.

Many reasons can be invoked, some may seem more plausible

than others but plausibility is a fairly subjective notion.

It would be useful to know whether the "bounty jumpers"

(i.e. those who enlisted, got their bounty, deserted, enlisted

again in another regiment, got a second bounty, and so on)

represented a substantial proportion of the deserters.

If so a better identification of those who enlisted could

prevent bounty jumping.

Q

Widows whose husbands were executed

The claims presented by emigrated Loyalists to the Claims

Commission set up by the British government

for the purpose of awarding compensations to Loyalists

are an interesting

source because it is completely independent from

American sources. Most of the claims describe losses incurred

through the expropriation of Loyalists. However, some 10%

of the claims were presented by widows or descendants and refer

in a broad way

to deaths resulting from being a Loyalists. Among such causes of

death one can distinguish:

In the following file some twenty cases are described.

Widows whose husbands were executed

The previous list has two important limitations.

We have used two sources: firstly a partial compilation published

in book format by P.W. Coldham (1980); secondly an Internet

source which reports mostly Canadian cases.

R

Executions of civilians in New York

In New York

between 1777 and 1783 there were some 21 death sentences issued by

courts martial against civilians. The source is Wiener (1967).

Below is a list of their names.

ABRAHAMS (Moses),

S

Anti-Loyalist mob actions in New York

(June 1776)

References

Allaire (A.) 1781: Diary of Lt. Anthony Allaire in the form of a

letter dated Charlestown, 30 January 1781

and published in the "Royal Gazette" of 24 February 1781.

Allaire (A.) 1881: Diary of Lt. Anthony Allaire. published

in "King' Mountain and it's heroes" edited and

published by Lyman Copeland Draper.

During the march the men were obliged to give 35

Continental dollars for a single ear of Indian corn, and 40 for

a drink of water, they were not allowed to drink when fording a

river.

Several of the [Loyalist] militia

that were worn out with fatigue, and not

being able to keep up, were cut down, and

trodden to death in the mire.

The Rebel officers would often go in amongst the prisoners,

draw their swords, cut down and wound those whom their

wicked and savage minds prompted.

Without these sentences it would appear to be an ordinary march.

When these sentences are added it seems rather a terror march.

We are told that many prisoners tried to escape; while some were

shot, a substantial number succeeded.

Allaire (A.) 1968: Diary of Lt. Anthony Allaire of Ferguson Corps.

Arno Press.

Coldham (P.W.) 1980: Almerican Loyalist claims. Published by

the "National Genealogical Society", Washington D.C.

Davis (R.S.) 1979: The Loyalist trials at Ninety Six in 1779.

South Carolina Historical Magazine p.172-181.

Jones (T.) 1879: History of New York during the Revolutionary War

and of the leading events in the other colonies at that period.

Edited and notes by Edward Floyd de Lancey.

Vol.1: 872p. Vol.2: 826p.

Printed for the New York Historical Society.

Greer (D.) 1934,2014: Incidence of the Terror during the French

Revolution. A statistical information.

Harvard University Press.

Maas (D.E.) 1989: The return of the Massachusetts Loyalists.

Garland Publishing, New York.

[Despite its title only two chapters in 11 are devoted to the return

of some of the Loyalists]

Moore (F.) 1860: Diary of the American Revolution. From newspapers

and original documents. New York.

[The author was a 19th century journalist and compiler. The reference

that he gives for the hanging of John Roberts is "Clift's Diary",

but we could not find it.]

O'Keefe (K.J.) 2011: Mass incarceration as Revolutionary policy.

The imprisonment of the Hudson Valley Loyalists.

Early American Studies 19,3,495-527.

Sanderson (J.) 1823: Biographies of the signers of the Declaration

of Independence. 4 vols. The biography of James Hamilton Jr Heyward

is in vol.4.

Wiener (F.B.) 1967: Civilians under military justice. Especially

in North America during the Revolution.

University of Chicago Press.

Wikipedia: article in English entitled: "Invasion of France (1795)"

B

Death sentences in state trials of Loyalists

C

Draft of "Forging consensus" with a list of executions

D

Death sentences by court martials

E

Control of suspected Loyalists in Albany county

F

Number of imprisoned Loyalists

(to be completed)

G

South Carolina Loyalists

H

Hunting down Loyalists in special courts and O&T courts

I

Parallel between SC and the French Vendee

J

British goal in Brittany landing

K

Civil war features of the Revolution in SC

L

Epuration of the Loyalists

M

The spiral of retaliations

N

List of names of 300 Loyalist victims in SC

O

Names of about 4,000 Loyalists in NY state

P

Evolution of desertion (1776-1782)

References

(i) Firstly, there was a great difference in population:

some 20 millions in France against some 2 millions (without the

slaves) in America.

(ii) Secondly, whereas in France religion was a major factor

of division within the French population, in America almost

all Anglican ministers were Loyalists.

In other words, religion

was not a distinct additional factor of division.

With respect to historiography the situation can be summarized

as follows.

In terms of increasing accuracy there are three levels of

description.

(a) Minimal anecdotal description.

(b) Exhaustive anecdotal description.

(c) Global description based on reliable global data.

List of 50 prisons

Jailing suspicious characters was the easiest and most

common way to get rid of the threat they may have represented.

Depending upon the outrage, it could be for a term

of one, six, nine, 12 months or more. In practice the term

was conditioned by the ability of the person to

provide a security, that is to say a guaranty in the form of

a sum of money. Often it was a joint guaranty in the sense

that a part of the money was provided by a friend.

Elusive Loyalists (p.40-42)

Mass-trials, sentences and pardons

Forging consensus.

The American Revolution in Loyalist perspective

contains a very provisional

version of the manuscript of a book in which the American

Revolution is considered from a Loyalist perspective.

As a third case we consider also the fate

of the persons (often German immigrates) who did not

wish the United States to take part in the First World War.

The fight against communism provides still another example of

how to eliminate dissenters. This part has yet to be written.

The Quakers in the Revolution

Former uprisings in several of the thirteen colonies

Tar-and-feather episodes

British judges and officials left at the mercy of the mobs

Imprisonments

Death sentences and executions

Identification of pardons

The numbers per year are as follows (provisional):

1776:1 1777:51 1778:50 1779:58 1780:56 1781:38 1782:20 1783:2

Total for 1776-1783: 276 executions

Acts of attainder and their consequences

Putting New York afire

The draft uprising in New York

During the war confiscation of German assets in America

Appendix: Civilian Patriots against Loyalists (based on Peter Force)

It is well-nigh inexplicable that so little remains

of the vast amount of

minutes and related records of this State body, existent in 7

counties and operative during about 5 years of the war. The several

boards were obligated by statute to keep accurate minutes of all of

their proceedings, subject to review by higher authority.

(FAMILY-NAME Given-name) page (month-year) Event description

These standardized events can be found in the following files:

First Commission, vol.1

Sometimes, after being arrested for no other reason than

the complaint of a neighbor, they were released after

one or two days; of course after having taken the oath

and having given security.

Usually, those who did not wish to take the oath

were imprisoned until they were willing to take it.

These individuals can be labelled as being real

Loyalists.

Coldham (P.W.) 1980: American Loyalist claims. National

Genealogical Society, Washington D.C. (616p.)

The main part of these claims consists in an enumeration of

forfeited property and confiscated estates. However, the accounts

also shortly mention possible stays in prison as proofs

of Loyalist status. By counting the number of imprisonment mentions

it becomes possible to estimate the number of imprisoned

Loyalists.

It can be called a death march for

according to the testimony of Anthony Allaire, a British Lieutenant,

those who

were unable "to keep up were trodden to death in the mire".

How many died is not revealed. One should remember that there were

some 700 prisoners and that 160 of them had been injured in

the fighting.

The number of deaths during the march may have surpassed

the number of those who were executed but as no data were

recorded or kept we will never know.

So far, we have never seen any official death

rate data for such episodes. Naturally, on weakened organisms, both

disease and exertion had deadly effects.

What led to this situation?

This method is very easy but it relies on the

assumption that the number of desertions by page remains

fairly uniform. As the index gives the page numbers for all

individual deserters one can also count the number of deserters in each

time interval. This leads to the curve in red. The fact that the

two curves are fairly parallel shows that the first method was

also fairly satisfactory.

This method is very easy but it relies on the

assumption that the number of desertions by page remains

fairly uniform. As the index gives the page numbers for all

individual deserters one can also count the number of deserters in each

time interval. This leads to the curve in red. The fact that the

two curves are fairly parallel shows that the first method was

also fairly satisfactory.

(i) deaths due to difficult imprisonment conditions.

(ii) killings by Patriot mobs

(iii) legal executions.

(i) The claims give little information about the specific

circumstances of the death. For instance, very often the

year of the death is not given.

(ii) At the time of writing (16 June 2024) it seems that

no

exhaustive compilation of the claims has been published.

Whereas for property losses this limitation is not crucial

for our present project it is a major defect.

"inh" means inhabitant whereas "ref" means refugee.

ALGER (Isaac) ref,

CHANDLER (Solomon),

CABROL (David) inh,

COLLINS (Richard),

DONNALY (Cornelius),

FARREN (John),

FERNE (John) inh,

FOGWELL (George),

GARRETSON (John),

GELLIN (John) inh,

GUFFIE (James),

HARDING (Jesse),

MASON (John),

McINTIRE (John),

McNEAL (Mary) inh,

NORMAN (Isaac),

PARKER (Nathaniel) ref,

PURDY (John),

RANDEN (Thomas),

ROACH (James) inh.

[Lt. Allaire was a British officer.

His testimony covers

the period from 1 September to 30 November 1780 which includes

the battle of Kings Mountain (7 Oct), a surprise attack

which was a Patriot victory and led to some 700

Loyalist prisoners of war.

In the weeks which followed the battle the prisoners

were marched to a stockade.

There is another version of this testimony which was published

one century later; see the next reference.

[Lyman Draper was an American historian who collected

documents or testimonies by individuals who played

a role in historic events. Sometimes, when the persons

were no longer living, he recorded the testimonies

of their sons or daughters.]

This is a rephrased version of the one of 1781.

We do not know how it was set up but it can be observed that

a number of crucial sentences have been omitted among which

are the following:

On the morning of the 15th October, Col. Campbell [Patriot leader]

had intelligence

that Col. Tarleton was approaching. He gave orders to his

men, that should he come up with them, they were

immediately to fire on Capt. Depeyster [Loyalist leader]

and his officers, who were

in the front, and then a second volley on the men.

[This publication reproduced the sanitized text of 1881.]

Boyle (J.L.) 2009: "He loves a good deal of rum ...".

Military desertion during the American Revolution.

Vol.1: 1775-1776, Vol.2: 1777-1783. Genealogical Publishing Company.

Baltimore.

[The term "Loyalist" does not appear in the title, but

Judge Thomas Jones was a prominent Loyalist. He wrote this

history between 1783 and 1787 while being a refugee in England.

It was only published about a century later.

Apart from general historical events, the book describes also

events of particular concern for the Jones and de Lancey families.]

Lambert (R.S) 1987: South Carolina Loyalists in the American

Revolution. University of South Carolina Press. Columbia (SC).

[A very lucid and well documentated account but the reader

has often the impression that the author knows more

than he wishes to say. Therefore some episodes which would

be of the highest interest remain shrouded in uncertainty.]